|

It hurt even navigating in that file, lest changing something or adding features.

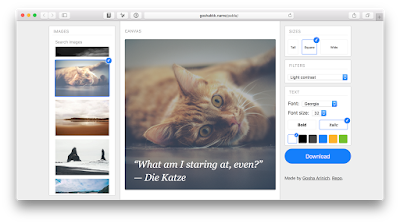

So with Pabla, I set to find better ways to make that happen.

If you are looking for a before-after, here you go:

Before — is very imperative and handles a lot of detail.

After — with all these nested components, it looks like any React code you are used to. It also allows you to define custom canvas components, with state and such! The Cursor component neatly encapsulates the blinking.

<Canvas width={canvasWidth} height={canvasHeight}>

<CanvasImage image={image} frame={mainFrame} />

<Filter name={filter} frame={mainFrame} />

<CanvasLine color={color} width={2} from={a} to={b} />

<CanvasLine color={color} width={2} from={a} to={b} />

</Canvas>In this post, I’m going to share what I learned about the private APIs of React that let it happen. While I will share some thought-process that led me there, some mid-steps will naturally be omitted.

🚧 The APIs discussed in this post are not public, and can/will change in the future.

Skip that if you are in for the reference and not the story.

(I am aware of projects like react-canvas. However, it seemed to have a different use-case in mind. That said, I did learn on some private React APIs from it.)

Declarative first

The goal is to go from imperative to React-style declarative. But do you know what would the first step be?

It’d be to go just declarative first. That is, using data structures to describe what should be drawn onto the canvas, not immediately drawing.

It is going from

drawImage(ctx, img, [0, 0, 300, 300]);

drawRect(ctx, "black", [10, 10, 290, 290]);[

{

type: 'image',

frame: [0, 0, 300, 300],

image: img

},

{

type: 'rect',

frame: [10, 10, 290, 290],

color: "black"

}

]This was a vast improvement already in terms of readability and understanding what’s going on.

It did lack, well, components — the layout had to include all the primitives. It’s true that these could be encapsulated into functions which return parts of this layout, and composing them together, but components are a bit more than on the screen, they’re also about encapsulating particular behavior (like the blinking cursor that I linked).

So what would it take to make it all React-y?

React renderers — high-level intro

It’s not a secret that React can be used to render to anything, even native mobile apps, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that you can make it render onto canvas.

React is a great generalization of UI, independent of the platform.

Before going into the details, let’s take a higher level look at what we need here, and really, what any rendered consists of.

|

- A bridge.

React DOM and React Native don’t need it. In this case of canvas, however, we will need to provide a place for canvas components to exist. For that, a bridge component is required. It’s a typical React component, which renders to DOM (with <canvas /> in this case.) What makes it unique is that, instead of putting its children into the DOM, it does something else to them, entirely.

- A group core component.

Can you imagine what the web would look like if you couldn’t group things — text and images — into blocks, and these block — into other blocks, and so on? No, nobody does that. So there are tags like div and p and a and so on — that can contain text or other elements. Your custom renderer needs that, too. To group primitive components into a single one that makes sense for your app.

- A primitive core component.

This is what you use to bridge primitives with React. In case of canvas, primitives will be like a rectangle, an image, a line of text, a line.

These are what every renderer has to have to be useful.

With that established, we can build on top of that with React components. Yes, the ones that you already write with class X extends React.Component or React.createClass or functions. They will work with no additional steps required once the baseline renderer is established.

Data structure

Now that that’s clear, let’s add a bit more detail and talk about how we are going to represent that.

- It’s evident that the structure we are dealing with here is a tree:

- Bridge

- Group 1

- Image

- Text

- Path

It’s like DOM! And in fact, that’s what React is working on — trees.

Now, the object structure that I’ve shown previously is immutable and can be great when it gets to the actual drawing… But when we need to insert a node here, or remove a node there, we better have a mutable tree (again, like DOM) in place.

For the tree, we are going to need several kinds of nodes:

- primitive, that represents a primitive data structure. It contains the primitive type and the props for drawing that.

- group, that represents a group of nodes.

- and bridge, that is a special kind of a group node that handles the drawing of its children.

These nodes are going to map to primitive/group/bridge components 1-to-1.

Concerning operations on nodes, what we are going to need is:

- insert a node into a group (in the beginning or after a certain node)

- remove a node

- render the whole tree

Here’s how I implemented these in Pabla.

The React bridge

|

There are two kinds of these:

- composite, which are created for every React.Component subclass

- platform-specific components aka host components (like div for DOM, Text for Native, or Rect for canvas)

An internal instance is an object with the following methods:

- constructor accepting a react “element” (which is a wrapper for props)

- mountComponent — called when a component is mounted

- receiveComponent — called when a component is updated

- unmountComponent — called when a component is unmounted

Naturally, we are looking to create custom host components for the group and primitive components.

To implement custom child rendering, we are going to need

ReactMultiChild.ReactMultiChild is a private mixin that a container component should extend to handle its children in a custom fashion.Bridge and group are both “containers”, i.e. components that handle child rendering.

Group and primitive are both “nodes”, i.e. things that are drawn.

It makes sense to extract that shared code into ContainerMixin and NodeMixin respectively.

Container

A few important methods that a container has to define are:

- moveChild(child, afterNode, toIndex, lastIndex) — used to reorder children inside a container OR to insert a new child

- removeChild(child) — used to remove a child node from the container

And there’s also some boilerplate that needs to be there:

mountAndInjectChildren(children, transaction, context)

updateChildren(nextChildren, transaction, context)

For a group and primitive components, which are going to be custom class components, we are going to store several properties:

_currentElement — to hold a reference to a react element

node — to store the node data structure we’ve defined previously

_mountImage — to also store the node

And have these methods:

- construct(element) — to set _currentElement

- getNativeNode() and getPublicInstance() — to get the backing node

- applyNodeProps(props) — which we’ll need to transfer the props to the node data structure

Bridge

The bridge will be using componentDidMount and receiveComponent to create/update the backing node, and construct children nodes.

Group

On group specifically, mountComponent and receiveComponent are needed to create/update the backing node, and construct children nodes.

Implementation

The post is not going to contain huge chunks of code.

You can use this file from Pabla as a reference for the full implementation.

Possible use cases

One other possible use case that hit me recently (and in a way, led to reflect on my canvas experience) is making a bridge from React Native to React, which will create a web view and render its children to it:

<ReactWebBridge>

<h2>Hey!</h2>

</ReactWebBridge>Source: reactjs

For more information , please support and follow us.

Suggest for you:

Build Web Apps with React JS and Flux

Modern React with Redux

Advanced React and Redux

Build Apps with React Native

The Complete Web Development Tutorial Using React and Redux

No comments:

Post a Comment